Early in the winter of 1996-97, impatient for the back-country snow to get deep, my friend Caleb and I set out to hike up the Wildcat Ridge Trail, across Pinkham Notch from the Presidentials, so we could ski down the manufactured snow of Wildcat Ski Area. For a lift-served area, Wildcat is pretty cool. It's not wicked developed, and it offers great views of the dramatic ridge on the opposite side of the notch.

Wildcat Ridge Trail is my favorite kind of trail. It doesn't waste your time slogging around on the approach. You go straight to the base of the ridge and then straight up the end of it. We wore our double boots and had the whole kit of winter mountaineering paraphernalia in case we needed it. In our packs we carried our Telemark boots. On a second trip I might just hike up in the ski boots, but this was our first survey of the route. It was nice to have the closer-fitting, stiff-soled boot for the steep or exposed bits.

It was sort of an anticlimax to pop out at the top of a ski lift after such a great rugged approach. Groomed snow seemed downright boring. But at least we got out for the day and we got to slide down, not slog.

We ran into a Tele clinic up there. I think it was Dick Hall's NATO (North American Telemark Organization). They're a fun bunch. A guy who looked a lot like Dick himself gave an approving grin when he saw us come trudging out of the woods all sugared with white from pushing our way through the snow-laden spruces.

We made our one run down and found a connecting trail that let us ski right back to Pinkham. Can't beat that for convenience.

These are memorable trips short and long by various modes of transportation, true to the best of my recollection.

Monday, December 19, 2005

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

A Modest Proposal

How about "Get Real Magazine," in which people look ordinary, think 5.7 rock is plenty hard enough, paddle Class I-III, ride less than 200 miles most weeks and never get to fly to Borneo or Chile?

I guess that would be pretty boring to read. It's fun to live, though.

I guess that would be pretty boring to read. It's fun to live, though.

Another Learning Experience in the Ravine

Random dredging in the journal turns up this one from April 1992:

Wayne and I got a late start because he had a dentist appointment, so we didn't leave his house until about 10:45. At Pinkham, the sun was shining and the snow was starting to soften.

Wayne forgot his climbing skins, so we hiked the Tuckerman Ravine Trail instead of skinning up the Sherburne. Running off at the mouth the way we do, it wasn't too tedious.

We stopped for lunch about two thirds of the way up at a sunny bridge. Old ski tracks ran down the river beneath it. We poked the snow. It seemed to be softening even that high up the mountain. With hopes intact, we continued up to Hojos (Hermit Lake caretaker cabin).

Three other pinheads lounged in the sun. We scanned the snowy heights. Wayne raved about the amount of snow.

The sun gleamed off of crust. Only Hillman's Highway showed many ski tracks. We could see isolated tracks from traverses and explorations around the Little Headwall, but the cold weather had prevented avalanches from stabilizing the upper slopes.

After boot and clothing adjustments and a quick visit to The Incredibly Stinky Outhouse, we started hiking up Hillman's with Wayne well ahead.

The snow was like concrete. The tracks of past skiers were frozen solid, waiting to trap anyone who could not jump out of their grasp. But first we had to climb up if we were going to ski down.

The higher I climbed up, the less I wanted to ski down. The wind howled up the slope behind us. A continuous avalanche of mostly pea-sized ice pellets pelted down on us.

Some alpine skiers had been on the Highway since before we arrived, and now began their last run down. Their metal ski edges rasped over the solid ice of the trail.

Wayne said he didn't want to go any higher about 300 feet above the point where I'd already left my balls behind. He perched beside the broad expanse of trail. I joined him.

With friendly greetings, the alpiners scraped by, jump-turning down to where the trail entered the trees. The windswept, icy ravine walls towered above us. The wind buffetted us as clouds surged across the headwall and blocked the sun. I looked down and felt only fear.

I got my right ski on. I'd had to remove my pack to get the skis off it. Perched on the slope with almost no purchase on the porcelain, I wondered if I would be able to get my left ski and my pack on before I fell down the hill. I wondered if I had bitten off more than I could chew. I wondered if it would chew me.

Teetering on my skis, I hoisted my pack and settled it on my hips and shoulders, adjusting the various straps and buckles as the wind punched at me. Satisfied my pack was snug, I bent to pick up my poles and felt the suspenders pop off the back of my trousers and shoot up inside the back of my jacket to make an uncomfortable lump.

I wasn't about to doff my pack, so now I was about to try to ski the most extreme terrain I had ever faced, with the crotch of my wind pants sagging halfway to my knees. This would at least insure a close lateral stance, as the textbooks advise.

I began to traverse to the left, sank down, planted my poles and launched.

Boom. I landed it, traversed, sank down, launched, landed, sank down, traversed, launched and fell. I wasn't going fast, so I didn't slide far, only smashed my right hip and elbow. I rose again, cleared my head and launched. I managed three or four turns between crashes and did a lot of plain sideslipping. Wayne watched, cheering and critiquing my efforts. I could barely hear him with the wind.

As a developing student skier, regardless of my advanced age, I figured my first objective was to come out on my own feet, not a Stokes litter. That I achieved. And a handful of years later I was jumping merrily down the upper reaches of Raymond Cataract and getting happily lost in the woods in search of glades no one else knows. And few people still do. So keep practicing. Eventually it falls into place. Or you get yourself killed. Either way, problem solved. The fascination no longer rules your every waking minute and lucid dream.

Wayne and I got a late start because he had a dentist appointment, so we didn't leave his house until about 10:45. At Pinkham, the sun was shining and the snow was starting to soften.

Wayne forgot his climbing skins, so we hiked the Tuckerman Ravine Trail instead of skinning up the Sherburne. Running off at the mouth the way we do, it wasn't too tedious.

We stopped for lunch about two thirds of the way up at a sunny bridge. Old ski tracks ran down the river beneath it. We poked the snow. It seemed to be softening even that high up the mountain. With hopes intact, we continued up to Hojos (Hermit Lake caretaker cabin).

Three other pinheads lounged in the sun. We scanned the snowy heights. Wayne raved about the amount of snow.

The sun gleamed off of crust. Only Hillman's Highway showed many ski tracks. We could see isolated tracks from traverses and explorations around the Little Headwall, but the cold weather had prevented avalanches from stabilizing the upper slopes.

After boot and clothing adjustments and a quick visit to The Incredibly Stinky Outhouse, we started hiking up Hillman's with Wayne well ahead.

The snow was like concrete. The tracks of past skiers were frozen solid, waiting to trap anyone who could not jump out of their grasp. But first we had to climb up if we were going to ski down.

The higher I climbed up, the less I wanted to ski down. The wind howled up the slope behind us. A continuous avalanche of mostly pea-sized ice pellets pelted down on us.

Some alpine skiers had been on the Highway since before we arrived, and now began their last run down. Their metal ski edges rasped over the solid ice of the trail.

Wayne said he didn't want to go any higher about 300 feet above the point where I'd already left my balls behind. He perched beside the broad expanse of trail. I joined him.

With friendly greetings, the alpiners scraped by, jump-turning down to where the trail entered the trees. The windswept, icy ravine walls towered above us. The wind buffetted us as clouds surged across the headwall and blocked the sun. I looked down and felt only fear.

I got my right ski on. I'd had to remove my pack to get the skis off it. Perched on the slope with almost no purchase on the porcelain, I wondered if I would be able to get my left ski and my pack on before I fell down the hill. I wondered if I had bitten off more than I could chew. I wondered if it would chew me.

Teetering on my skis, I hoisted my pack and settled it on my hips and shoulders, adjusting the various straps and buckles as the wind punched at me. Satisfied my pack was snug, I bent to pick up my poles and felt the suspenders pop off the back of my trousers and shoot up inside the back of my jacket to make an uncomfortable lump.

I wasn't about to doff my pack, so now I was about to try to ski the most extreme terrain I had ever faced, with the crotch of my wind pants sagging halfway to my knees. This would at least insure a close lateral stance, as the textbooks advise.

I began to traverse to the left, sank down, planted my poles and launched.

Boom. I landed it, traversed, sank down, launched, landed, sank down, traversed, launched and fell. I wasn't going fast, so I didn't slide far, only smashed my right hip and elbow. I rose again, cleared my head and launched. I managed three or four turns between crashes and did a lot of plain sideslipping. Wayne watched, cheering and critiquing my efforts. I could barely hear him with the wind.

As a developing student skier, regardless of my advanced age, I figured my first objective was to come out on my own feet, not a Stokes litter. That I achieved. And a handful of years later I was jumping merrily down the upper reaches of Raymond Cataract and getting happily lost in the woods in search of glades no one else knows. And few people still do. So keep practicing. Eventually it falls into place. Or you get yourself killed. Either way, problem solved. The fascination no longer rules your every waking minute and lucid dream.

Tuesday, August 30, 2005

It Feels Good Because it is Good

The best thing most of us could do for the environment is to die. So that leads us to the second best thing.

How does one consume less, pollute less and take up less space and still have a good time?

Maybe you have to redefine a good time. But you can still have fun.

You can do a lot by eliminating motors as much as possible. You can do a lot without a motor.

Sailboats can move pretty fast when the wind is right. Whitewater kayaks use natural forces to propel them through a challenging environment.

You can even skydive without using motors. Just BASE jump, using tall objects to gain your elevation.

Motorized recreation attracts people because it makes speed convenient and it makes it seem safe. But how safe is it, really?

It’s fun to drive like an asshole. I’ve been doing that for as long as I’ve had a driver’s license. But a sense of responsibility keeps me from doing it as much as I used to, and I never really went as far as I could. I still understand the compulsion.

If you push the margins of safety in motor vehicles, you might as well go into other dangerous activities and try to eliminate the motor. Jump off a cliff. Sail in a gale. Challenge yourself. Try to surf the wakes of really big ships with your kayak.

Human-powered recreation leads to physical fitness. Motorized recreation leads to physical deterioration.

If you’re not a thrill-seeker, you put even less pressure on your fun and games to stimulate adrenaline. You can walk, hike, swim, sail, paddle, row or cycle just for the pleasure and sense of accomplishment, and the feeling of vitality that always comes from physical activity.

How does one consume less, pollute less and take up less space and still have a good time?

Maybe you have to redefine a good time. But you can still have fun.

You can do a lot by eliminating motors as much as possible. You can do a lot without a motor.

Sailboats can move pretty fast when the wind is right. Whitewater kayaks use natural forces to propel them through a challenging environment.

You can even skydive without using motors. Just BASE jump, using tall objects to gain your elevation.

Motorized recreation attracts people because it makes speed convenient and it makes it seem safe. But how safe is it, really?

It’s fun to drive like an asshole. I’ve been doing that for as long as I’ve had a driver’s license. But a sense of responsibility keeps me from doing it as much as I used to, and I never really went as far as I could. I still understand the compulsion.

If you push the margins of safety in motor vehicles, you might as well go into other dangerous activities and try to eliminate the motor. Jump off a cliff. Sail in a gale. Challenge yourself. Try to surf the wakes of really big ships with your kayak.

Human-powered recreation leads to physical fitness. Motorized recreation leads to physical deterioration.

If you’re not a thrill-seeker, you put even less pressure on your fun and games to stimulate adrenaline. You can walk, hike, swim, sail, paddle, row or cycle just for the pleasure and sense of accomplishment, and the feeling of vitality that always comes from physical activity.

Monday, August 08, 2005

Hummingbirds, for some reason

One spring day in 1990, I noticed a hummingbird investigating the brightly-colored outdoor thermometer on the back of my house. Always a fan of the little sugar hawks, I broke out a couple of little feeders from storage. I'd hung them outside of other places I'd lived, and considered myself lucky if I'd get to see one or two a season.

Living in the piney woods, I was surprised to see a hummingbird at all. Imagine my astonishment when I soon had several at a time, day after day, all summer. Apparently, they like to nest in the shelter of the evergreens. Now my gardening wife has planted many flowers, but the breeding population showed up without any incentive I could see. They certainly seem to enjoy the feeders, if enjoy is the right word for the twittering dogfights that make up their day.

The first one, usually a male, shows up on May 12th each year as if by appointment. It may not be exactly the 12th in a given year, but it usually is. Days will pass with just the single bird, and then another. By the end of May the whole crowd has arrived. The buzzing and twittering joins the calls of phoebes and other nesting songbirds busy with the rites of spring.

They're insane. They battle constantly. Then, suddenly, peace will break out and two or more will land and sip amicably. The truce will last for minutes before everyone launches again.

They eat during the battles as well. Usually, a dominant bird will defend the feeder against all comers. You can actually hear them slam into each other. One day I came out the door to find one squirming on the ground. I thought the cat might have made a lucky pounce, but then I heard the other bird. It had simply knocked the loser out of the sky. The one on the ground gathered its wits and charged back into the air.

We just put a seed feeder out on the other side of a double hook in one of the flower beds. Chickadees and nuthatches look huge after watching hummingbirds for a couple of months.

Living in the piney woods, I was surprised to see a hummingbird at all. Imagine my astonishment when I soon had several at a time, day after day, all summer. Apparently, they like to nest in the shelter of the evergreens. Now my gardening wife has planted many flowers, but the breeding population showed up without any incentive I could see. They certainly seem to enjoy the feeders, if enjoy is the right word for the twittering dogfights that make up their day.

The first one, usually a male, shows up on May 12th each year as if by appointment. It may not be exactly the 12th in a given year, but it usually is. Days will pass with just the single bird, and then another. By the end of May the whole crowd has arrived. The buzzing and twittering joins the calls of phoebes and other nesting songbirds busy with the rites of spring.

They're insane. They battle constantly. Then, suddenly, peace will break out and two or more will land and sip amicably. The truce will last for minutes before everyone launches again.

They eat during the battles as well. Usually, a dominant bird will defend the feeder against all comers. You can actually hear them slam into each other. One day I came out the door to find one squirming on the ground. I thought the cat might have made a lucky pounce, but then I heard the other bird. It had simply knocked the loser out of the sky. The one on the ground gathered its wits and charged back into the air.

We just put a seed feeder out on the other side of a double hook in one of the flower beds. Chickadees and nuthatches look huge after watching hummingbirds for a couple of months.

This file photo from about ten years ago shows pretty good attendance at the feeder array I had at the time. It's nearly impossible to get a shot of the full action. Last week at breakfast time a cloud of at least half a dozen swirled around the one big feeder hanging outside the kitchen window.

Posted by Picasa

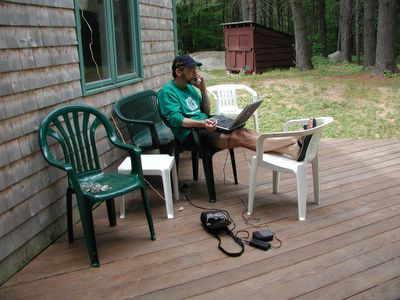

I was using my outdoor office this afternoon, when a hummingbird flew in from my left. It hovered in front of me for many seconds, quite a long time in hummingbird time, looking up and down, back and forth, scrutinizing the details of my setup. Apparently satisfied, it leveled off and flew away to a nearby feeder. This is a file photo from last year. I'm sweltering in a blue tee shirt today. Hazy, hot and humid, as cicadas zizz in the tropical trees.

Posted by Picasa

Monday, July 25, 2005

This Afternoon at Sebago

In a rare escape, Laurie and I managed to slip away to Sebago Lake on July 12. Finding the park entrance was a bit of a treasure hunt, but we got there eventually.

Laurie did not grow up in small boats, the way I did, so she does not have a well-tuned sense of her ability and of the actual danger posed by weather conditions. She's a good boater, but doesn't have the context to know it and appreciate it. So I didn't say anything when I saw the flags blowing out straight. So much of danger is a matter of perception. Too much of the wrong kind of fear actually creates danger. Better to poke out and see, rather than influence the mood by playing it up or down.

"It wasn't choppy on the map," she said as we emerged from the aptly named Crooked River. But she calmed considerably when I pointed out that if she dumped she could easily walk to shore. The sand bar shelved out for many yards. The bigger waves had tripped and stumbled on the outer margin of these shallows, so we rode only the half-size remnants. They were steep, but small.

We ventured along the shore, with no particular destination. When a cove opened to our left, we turned to surf into it. A couple in a canoe was entering it from the opposite direction. I would not really have wanted to be in an open boat with no flotation in the larger waves further out in the lake, but I didn't see where they started, so I don't know how long they dealt with it.

As regulars on Winnipesaukee, we were amazed to find that the white beach at the back of the cove was part of the park, so we could land and have lunch. What's the matter? Not enough rich people in Maine to buy and fence off the shoreline? Let's enjoy it.

After lunch and a bit of shore exploration, where Laurie enjoyed childhood memories of a family trip to Sebago Lake in the mid 1960s, we set out again to go a little further down the exposed shoreline. We didn't have a ton of time to play that day, but we wanted to get a little more wave time.

Beyond the lunch cove the waves were bigger than we'd seen so far. The water was deeper and they'd run the length of the lake.

After we rounded the next point, we curved around behind a small island, nearly a peninsula. Waves broke over the teeth of rocks in the shallows that nearly connected it to the mainland, so we went around the end. Then we came in behind it to play in the wind-generated current pouring through over the rocks.

After a few minutes in shelter, we emerged to head back to the river. Enroute, Laurie suddenly diverted shoreward.

"I'm going to swim!" she called, indicating the floats of a swim beach. Everyone had left it as the afternoon waned. I rode in behind her to a wet landing on the beach. Waves swept the length of the boat as soon as it stopped at the sand. We had to hop out and drag our boats up fast, to avoid getting a cockpit full of water.

After splashing around the swim beach for a while we boarded again. Laurie challenged herself by getting aboard out in the water. She did it without any unscheduled additional swimming.

Wind and waves came from the most troublesome angle on the last leg. The short, the steep and the ugly kept trying to make our rudderless boats yaw. I've learned that you can ride the oscillation and maintain your average heading more efficiently than rigidly trying to stop every deviation. It doesn't seem to be something that can be taught, only discovered for oneself.

The waves going into the river acted like conflicting wind and tide. The river didn't seem to have much current, but it was enough, with the wind and the shallows, to make some weird stuff.

Once inside, we were able to outdistance a motor boat admirably observing headway speed. We coasted to a peaceful finish. Nice afternoon.

Laurie did not grow up in small boats, the way I did, so she does not have a well-tuned sense of her ability and of the actual danger posed by weather conditions. She's a good boater, but doesn't have the context to know it and appreciate it. So I didn't say anything when I saw the flags blowing out straight. So much of danger is a matter of perception. Too much of the wrong kind of fear actually creates danger. Better to poke out and see, rather than influence the mood by playing it up or down.

"It wasn't choppy on the map," she said as we emerged from the aptly named Crooked River. But she calmed considerably when I pointed out that if she dumped she could easily walk to shore. The sand bar shelved out for many yards. The bigger waves had tripped and stumbled on the outer margin of these shallows, so we rode only the half-size remnants. They were steep, but small.

We ventured along the shore, with no particular destination. When a cove opened to our left, we turned to surf into it. A couple in a canoe was entering it from the opposite direction. I would not really have wanted to be in an open boat with no flotation in the larger waves further out in the lake, but I didn't see where they started, so I don't know how long they dealt with it.

As regulars on Winnipesaukee, we were amazed to find that the white beach at the back of the cove was part of the park, so we could land and have lunch. What's the matter? Not enough rich people in Maine to buy and fence off the shoreline? Let's enjoy it.

After lunch and a bit of shore exploration, where Laurie enjoyed childhood memories of a family trip to Sebago Lake in the mid 1960s, we set out again to go a little further down the exposed shoreline. We didn't have a ton of time to play that day, but we wanted to get a little more wave time.

Beyond the lunch cove the waves were bigger than we'd seen so far. The water was deeper and they'd run the length of the lake.

After we rounded the next point, we curved around behind a small island, nearly a peninsula. Waves broke over the teeth of rocks in the shallows that nearly connected it to the mainland, so we went around the end. Then we came in behind it to play in the wind-generated current pouring through over the rocks.

After a few minutes in shelter, we emerged to head back to the river. Enroute, Laurie suddenly diverted shoreward.

"I'm going to swim!" she called, indicating the floats of a swim beach. Everyone had left it as the afternoon waned. I rode in behind her to a wet landing on the beach. Waves swept the length of the boat as soon as it stopped at the sand. We had to hop out and drag our boats up fast, to avoid getting a cockpit full of water.

After splashing around the swim beach for a while we boarded again. Laurie challenged herself by getting aboard out in the water. She did it without any unscheduled additional swimming.

Wind and waves came from the most troublesome angle on the last leg. The short, the steep and the ugly kept trying to make our rudderless boats yaw. I've learned that you can ride the oscillation and maintain your average heading more efficiently than rigidly trying to stop every deviation. It doesn't seem to be something that can be taught, only discovered for oneself.

The waves going into the river acted like conflicting wind and tide. The river didn't seem to have much current, but it was enough, with the wind and the shallows, to make some weird stuff.

Once inside, we were able to outdistance a motor boat admirably observing headway speed. We coasted to a peaceful finish. Nice afternoon.

Just after launching at Sebago Lake State Park in Maine. The Aqua Pac camera bag already got wet, and steamed up inside until I could dry it out at our lunch stop. But the lake was rough, so I knew I needed to protect the camera.

Posted by Picasa

Notice how high her bow has been tossed. I only got this much because my boat was also riding over a wave.

Posted by Picasa

Laurie takes a quiet moment before we emerge from the shelter of a small island to begin our trip back down along the lee shore to where we started. The waves we're about to enter at this point have run the length of Sebago Lake.

Posted by Picasa

Bow tossed upward as we emerge from shelter. That oncoming wave face looks kind of serious from this angle.

Posted by Picasa

I was hoping I'd get this one: bow buried in the back of a wave, with Laurie just beyond it.

Posted by Picasa

There she is, obscured by the droplets on the front of the waterproof camera bag. Aqua Pac is cool!

Posted by Picasa

This is the last shot that really framed anything. I tried for that perfect shot of silhouetted kayaker on a path of sun sparkles after we got around the point, but my aim was off.

Posted by Picasa

Tuesday, June 14, 2005

Another Pointless Excursion

It was September 1997. After several years on a trailer in my father’s side yard, the Snipe class dinghy we had sailed together now lived in my garage. I had painstakingly worked out how to manipulate 225 pounds of hull by myself, so I could turn her over to refinish the bottom and turn her back over again.

Somehow, twelve years had sneaked by since I had sailed any boat, let alone this one. I’d lived inland, using a kayak on small waters. In that time my first marriage had run its course. Now I was alone, a middle aged guy with an elderly dog and a cat who thought she owned the place.

The middle of life gives a good view of both ends, perhaps too good a view. Some people get really crazy. Since I felt life was short and not to be wasted from the time I was ten, I had an advantage over people who had given it less thought. Every moment is precious. You can fill every minute with great achievement, which gives the impression the time has not been wasted, but what if you never gave yourself time to think? That’s when you slam into the wall at age 40 or 47 or 53 and find yourself sitting in the crumpled body of your sleek, powerful life, wondering what happened since your twenties.

I’d never been good at sailboat racing. I enjoyed the ride too much. But now I held the tiller and the main sheet – and the jib sheet, too, for that matter. My style would no longer inconvenience anyone else. No one human, anyway.

Winter Harbor on Lake Winnipesaukee does not offer an ideal launching site. All the ramps on this lake are built with motorboats in mind. They don’t need a place to rig. They don’t care if they’re on a lee shore. But with summer over, the Winter Harbor ramp was deserted. Traffic on Route 109 was light. The trailer parking is not half a mile away, so trailer handling was about as easy as it gets for the lone boater.

A stronger wind would have bashed up the boat while I was finishing rigging. The water was too shallow for me to ship the rudder until everything else was ready and I could hold the boat across the end of the short pier by the ramp.

Because I hadn’t done anything that day with my dog Lee, I had brought him with me to the lake. Now I had to get him aboard. He wanted to get near me, but couldn’t make the drop from the high pier. I encouraged him to swim out from shore and then hoisted him aboard, standing beside the boat in waist-deep water.

He was a bit disoriented in the boat. Once aboard, he stood dripping on the floorboards, on shaky legs, obviously wondering why he had wanted to be there. By then, however, we were underway.

The breeze was southerly, five to eight miles per hour, maybe ten. It was enough to heel the boat with me sitting to weather in the stronger puffs, but in the average wind I had to sit inboard, even prejudiced to leeward.

We headed out toward the mouth of Winter Harbor on a long port-tack reach that varied from close hauled to having the wind abeam. A couple or three motor boats buzzed around the fringes of the bay. Then an old classic wooden one began to overtake me. I heard a woman’s voice say, with some excitement, “that’s a Snipe!”

The woodie, “Clair de Loon,” came close enough to hail, more or less. I could hear them better than they could hear me. The woman, who did not give her name, had sailed Snipes years ago. She said her sail number had been 2677. She’d been looking for a wooden Snipe, but had to settle for a 23000 glass boat she’d purchased down at Buzzards Bay.

Because of the engine noise the conversation gave way to smiling and waving. Cordially, we parted.

Lee, while he did not become enthusiastic, did stoically stand in the cockpit for the outward passage. I had no clear plan, just a vague idea to get out to the open lake and see what we might find.

The boat had taken on a great deal of water. This was not surprising, since she’d been dry for years. I didn’t discover until later that the centerboard trunk was severely delaminated and slightly sprung. Unfortunately, only twice in the whole voyage did we hit a speed that made the suction bailers work. I kept having to burrow down in the bilges with a sponge. That made me less attentive to the constant wind shifts, so then I would have to focus on sailing for a while.

I also noticed things I hadn’t adjusted properly, or suddenly remembered to operate one control or another, like jib cloth, mast benders or jib halyard tension.

My emotions flashed up and down. This was not a triumphant culmination or a total joy. I thought about my father and our disappointing career in racing. I experienced now, alone with the boat and responsible for everything, how it must have been for him, trying to keep the boat in good repair and the control systems up to date, trying to remember all the gear and get it together before trips with so little involvement from me.

I enjoyed the trips, but I always hovered before one, wondering if I was ready physically, mentally, emotionally and in equipment. I did not embrace and merge with the world of sailboat racing. I knew a few names, but had no heroes. To a non-sailor I looked like a total disciple, but I knew the difference. If I had a hero at all it was my own father, who could get a boat into and out of anywhere, and got my vote as most likely to come safely through any situation we might encounter. Beyond that I didn’t care much who was whom. I would seldom go out with anyone else.

Not that service in the fo’c’sle of 11900 was a constant flow of fatherly wisdom and reassurance. Sometimes it felt a bit like the Eighteenth Century and I’d been snatched off a British street and come to my senses far offshore, with a raging hangover and a nasty bosun standing over me. But it can’t have been too easy for him, either. A complex man with many conflicting ambitions, he made the best he could of the brew he got by mixing them.

I should have guessed the boat would be saturated with the emotions that had soaked into her over the years of father and son racing. No surprise, either, that these should call forth many reflections on the years that had passed since, the many failures and few successes, the debatable achievement of 41 thoughtful years.

11900 is herself but a year younger than I am. She was 11 when we got her as a used boat, just as the class was about to undergo rule changes that would put her at a disadvantage for most of her remaining competitive years. As a vehicle for reclaiming my father’s considerable past glory she would present a challenge that would be exacerbated by his choice to use family members to crew.

None of this formed into words as I sailed out to the lake. I enjoyed the breeze, which just touched the top end of my ability to keep the boat upright with the full rig, but mostly blew much more softly. The sky was full of cumulus clouds, as a front seemed to try to pass. The sun settled toward the western horizon.

I felt more aware of the factors that shape a breeze than I had even been. I looked at the clouds, the land, and saw a map on the water before me. I’d wondered how great a time I could have with this poor, dried-out boat I’d resuscitated, and my own stale skills. But here I was, despite 40 gallons of water in the bilges and a dog who clearly wished he was somewhere else, slipping along through the fluky evening breeze, having a transformational experience.

Motorboats passed at a polite distance out on the open broads. The breeze had its most uninterrupted sweep there, too. I actually got to hike out a few times. Intoxicated by wind, wave and my interaction with them, I steered up close-hauled and even tacked a couple of times, edging toward Wolfeboro Bay.

Lee spoke up with a piteous howl. “That’s enough,” he seemed to say. “Take me home!”

In my terror-stricken early childhood I always howled much louder, much sooner.

He was right on one count. We had to head back to get to the launching ramp by dark. I had brought no lights and the breeze was getting fitful.

I bore off, pulled the centerboard up to three notches and tweaked what things I could to improve reaching. I’d left the whisker pole at home, because I figured it would be too much trouble singlehanding, but now I was broad reaching in light air and it would have been perfect. Fortunately, the wind shifted and the need passed.

I aimed to miss the wind shadow of Wolfeboro Neck, but the wind was dying even as I headed for the sheltered bight that leads to the inner lobe of Winter Harbor. The whole area turned into a wind shadow. What breeze there was came from a different direction each time and died out before I’d trimmed the sails to it.

I began to paddle. To keep going straight, I lashed the tiller a bit to starboard to compensate for my paddle strokes to port. As we gathered way, the apparent wind would back the jib. After twenty to forty paddle strokes I would stop, trim to the apparent wind and the boat would coast slowly to a near halt, the sails falling limp, fluttering indecisively.

The sun was sinking and so was the boat. I was getting chilly, since I was mostly wet. Darkness fell as the water in the bilges rose. I sponged some water at intervals, but didn’t really seem to gain.

A quarter moon hung in the sky behind me. Stars circled above the mast tip. A breeze whispered in. It was light but steady. I secured from paddling, unlashed the tiller and set about stalking it.

I sat to leeward with Lee’s head jammed into me, because he was cuddling for comfort. I watched the luff of main and jib. The breeze was still so light that mosquitoes and gnats could reach me from shore.

The boat undeniably moved smoothly and steadily through the deep dusk. This was artistic and satisfying. Loons I’d seen earlier called now. Bats flitted past me, snapping up the insects. I could hear the bats’ chirping navigational calls as they avoided my vessel, ghosting in the moonlight.

All the rigamarole of getting there had been worth it for that delicate close reach in the dark. I remembered night sailing in 420s with my younger brother and my friend Jim. I felt melancholy for the companions lost, but exhilarated by the artistry itself. Our launching point loomed suddenly near. What we had been so desperate to reach, and still wanted and needed to reach, was here, now, to end the magic flight on silent breeze.

I needed three tacks to gain the pier. Would a better sailor have done it in two? No matter. They were good tacks. Any landing you can walk away from is a good landing. We nestled beside the pier and I lifted my long-suffering canine back onto solid ground.

Somehow, twelve years had sneaked by since I had sailed any boat, let alone this one. I’d lived inland, using a kayak on small waters. In that time my first marriage had run its course. Now I was alone, a middle aged guy with an elderly dog and a cat who thought she owned the place.

The middle of life gives a good view of both ends, perhaps too good a view. Some people get really crazy. Since I felt life was short and not to be wasted from the time I was ten, I had an advantage over people who had given it less thought. Every moment is precious. You can fill every minute with great achievement, which gives the impression the time has not been wasted, but what if you never gave yourself time to think? That’s when you slam into the wall at age 40 or 47 or 53 and find yourself sitting in the crumpled body of your sleek, powerful life, wondering what happened since your twenties.

I’d never been good at sailboat racing. I enjoyed the ride too much. But now I held the tiller and the main sheet – and the jib sheet, too, for that matter. My style would no longer inconvenience anyone else. No one human, anyway.

Winter Harbor on Lake Winnipesaukee does not offer an ideal launching site. All the ramps on this lake are built with motorboats in mind. They don’t need a place to rig. They don’t care if they’re on a lee shore. But with summer over, the Winter Harbor ramp was deserted. Traffic on Route 109 was light. The trailer parking is not half a mile away, so trailer handling was about as easy as it gets for the lone boater.

A stronger wind would have bashed up the boat while I was finishing rigging. The water was too shallow for me to ship the rudder until everything else was ready and I could hold the boat across the end of the short pier by the ramp.

Because I hadn’t done anything that day with my dog Lee, I had brought him with me to the lake. Now I had to get him aboard. He wanted to get near me, but couldn’t make the drop from the high pier. I encouraged him to swim out from shore and then hoisted him aboard, standing beside the boat in waist-deep water.

He was a bit disoriented in the boat. Once aboard, he stood dripping on the floorboards, on shaky legs, obviously wondering why he had wanted to be there. By then, however, we were underway.

The breeze was southerly, five to eight miles per hour, maybe ten. It was enough to heel the boat with me sitting to weather in the stronger puffs, but in the average wind I had to sit inboard, even prejudiced to leeward.

We headed out toward the mouth of Winter Harbor on a long port-tack reach that varied from close hauled to having the wind abeam. A couple or three motor boats buzzed around the fringes of the bay. Then an old classic wooden one began to overtake me. I heard a woman’s voice say, with some excitement, “that’s a Snipe!”

The woodie, “Clair de Loon,” came close enough to hail, more or less. I could hear them better than they could hear me. The woman, who did not give her name, had sailed Snipes years ago. She said her sail number had been 2677. She’d been looking for a wooden Snipe, but had to settle for a 23000 glass boat she’d purchased down at Buzzards Bay.

Because of the engine noise the conversation gave way to smiling and waving. Cordially, we parted.

Lee, while he did not become enthusiastic, did stoically stand in the cockpit for the outward passage. I had no clear plan, just a vague idea to get out to the open lake and see what we might find.

The boat had taken on a great deal of water. This was not surprising, since she’d been dry for years. I didn’t discover until later that the centerboard trunk was severely delaminated and slightly sprung. Unfortunately, only twice in the whole voyage did we hit a speed that made the suction bailers work. I kept having to burrow down in the bilges with a sponge. That made me less attentive to the constant wind shifts, so then I would have to focus on sailing for a while.

I also noticed things I hadn’t adjusted properly, or suddenly remembered to operate one control or another, like jib cloth, mast benders or jib halyard tension.

My emotions flashed up and down. This was not a triumphant culmination or a total joy. I thought about my father and our disappointing career in racing. I experienced now, alone with the boat and responsible for everything, how it must have been for him, trying to keep the boat in good repair and the control systems up to date, trying to remember all the gear and get it together before trips with so little involvement from me.

I enjoyed the trips, but I always hovered before one, wondering if I was ready physically, mentally, emotionally and in equipment. I did not embrace and merge with the world of sailboat racing. I knew a few names, but had no heroes. To a non-sailor I looked like a total disciple, but I knew the difference. If I had a hero at all it was my own father, who could get a boat into and out of anywhere, and got my vote as most likely to come safely through any situation we might encounter. Beyond that I didn’t care much who was whom. I would seldom go out with anyone else.

Not that service in the fo’c’sle of 11900 was a constant flow of fatherly wisdom and reassurance. Sometimes it felt a bit like the Eighteenth Century and I’d been snatched off a British street and come to my senses far offshore, with a raging hangover and a nasty bosun standing over me. But it can’t have been too easy for him, either. A complex man with many conflicting ambitions, he made the best he could of the brew he got by mixing them.

I should have guessed the boat would be saturated with the emotions that had soaked into her over the years of father and son racing. No surprise, either, that these should call forth many reflections on the years that had passed since, the many failures and few successes, the debatable achievement of 41 thoughtful years.

11900 is herself but a year younger than I am. She was 11 when we got her as a used boat, just as the class was about to undergo rule changes that would put her at a disadvantage for most of her remaining competitive years. As a vehicle for reclaiming my father’s considerable past glory she would present a challenge that would be exacerbated by his choice to use family members to crew.

None of this formed into words as I sailed out to the lake. I enjoyed the breeze, which just touched the top end of my ability to keep the boat upright with the full rig, but mostly blew much more softly. The sky was full of cumulus clouds, as a front seemed to try to pass. The sun settled toward the western horizon.

I felt more aware of the factors that shape a breeze than I had even been. I looked at the clouds, the land, and saw a map on the water before me. I’d wondered how great a time I could have with this poor, dried-out boat I’d resuscitated, and my own stale skills. But here I was, despite 40 gallons of water in the bilges and a dog who clearly wished he was somewhere else, slipping along through the fluky evening breeze, having a transformational experience.

Motorboats passed at a polite distance out on the open broads. The breeze had its most uninterrupted sweep there, too. I actually got to hike out a few times. Intoxicated by wind, wave and my interaction with them, I steered up close-hauled and even tacked a couple of times, edging toward Wolfeboro Bay.

Lee spoke up with a piteous howl. “That’s enough,” he seemed to say. “Take me home!”

In my terror-stricken early childhood I always howled much louder, much sooner.

He was right on one count. We had to head back to get to the launching ramp by dark. I had brought no lights and the breeze was getting fitful.

I bore off, pulled the centerboard up to three notches and tweaked what things I could to improve reaching. I’d left the whisker pole at home, because I figured it would be too much trouble singlehanding, but now I was broad reaching in light air and it would have been perfect. Fortunately, the wind shifted and the need passed.

I aimed to miss the wind shadow of Wolfeboro Neck, but the wind was dying even as I headed for the sheltered bight that leads to the inner lobe of Winter Harbor. The whole area turned into a wind shadow. What breeze there was came from a different direction each time and died out before I’d trimmed the sails to it.

I began to paddle. To keep going straight, I lashed the tiller a bit to starboard to compensate for my paddle strokes to port. As we gathered way, the apparent wind would back the jib. After twenty to forty paddle strokes I would stop, trim to the apparent wind and the boat would coast slowly to a near halt, the sails falling limp, fluttering indecisively.

The sun was sinking and so was the boat. I was getting chilly, since I was mostly wet. Darkness fell as the water in the bilges rose. I sponged some water at intervals, but didn’t really seem to gain.

A quarter moon hung in the sky behind me. Stars circled above the mast tip. A breeze whispered in. It was light but steady. I secured from paddling, unlashed the tiller and set about stalking it.

I sat to leeward with Lee’s head jammed into me, because he was cuddling for comfort. I watched the luff of main and jib. The breeze was still so light that mosquitoes and gnats could reach me from shore.

The boat undeniably moved smoothly and steadily through the deep dusk. This was artistic and satisfying. Loons I’d seen earlier called now. Bats flitted past me, snapping up the insects. I could hear the bats’ chirping navigational calls as they avoided my vessel, ghosting in the moonlight.

All the rigamarole of getting there had been worth it for that delicate close reach in the dark. I remembered night sailing in 420s with my younger brother and my friend Jim. I felt melancholy for the companions lost, but exhilarated by the artistry itself. Our launching point loomed suddenly near. What we had been so desperate to reach, and still wanted and needed to reach, was here, now, to end the magic flight on silent breeze.

I needed three tacks to gain the pier. Would a better sailor have done it in two? No matter. They were good tacks. Any landing you can walk away from is a good landing. We nestled beside the pier and I lifted my long-suffering canine back onto solid ground.

Tuesday, May 31, 2005

Taken by the Waves

During my college years in Florida I was an addicted body surfer.

One summer day at New Smyrna Beach, we arrived from Orlando to find the biggest conditons I'd seen yet. The tide was fairly high and the white-crested surf piled up on itself as the waves rumbled ashore. It wasn't storm surf by any means, but it looked more powerful than the usual sea-breeze break of two- or three-footers we usually played out there on the bar.

Once we parked I hopped out, tossed down my towel, stripped to my shorts and sprinted down the sand.

Even the shore break felt powerful, but the good stuff was further out, where the bar break was building. Those waves always gave long, smooth rides and dumped into deeper water, so the landings were soft.

This day, I felt different forces in the water. It seemed darker and bluer, with whiter foam and stronger winds. The breakers curled up quickly, rearing over me. The tide was higher than it had looked. The bigger waves started to break in deeper water. I was neck deep in the troughs and the current sucked me along.

That's when I noticed the tiny, dancing figure of the life guard. I'd never really noticed the lifeguards on this beach before. I didn't bother them. They didn't bother me. But now I heard a thin little whistle fighting through the rumble of waves and the beating of the wind gusts over the breaking crests. The tiny figure on the tall chair waved urgently, imperatively, gathering me shoreward with his arm. Snap! Snap! It looked like the opposite of throwing a ball.

The current had me. I was on my way to Daytona. Worse than that, I was pissing off the lifeguard. Not good.

Not even a strong swimmer fights a current like that. You need endurance and patience, not explosive power. I lay over in a leisurely side-stroke and angled gently toward shore. The current would let me sidle out if I just took my time.

Once out of the main flow I caught a shore-bound breaker and rode in to a belly-landing on the beach. I walked about a quarter-mile back to the car.

It seemed like a good day to stay dry and work on the old tan. But I was glad I'd at least given the waves a try. It was a good little trip.

One summer day at New Smyrna Beach, we arrived from Orlando to find the biggest conditons I'd seen yet. The tide was fairly high and the white-crested surf piled up on itself as the waves rumbled ashore. It wasn't storm surf by any means, but it looked more powerful than the usual sea-breeze break of two- or three-footers we usually played out there on the bar.

Once we parked I hopped out, tossed down my towel, stripped to my shorts and sprinted down the sand.

Even the shore break felt powerful, but the good stuff was further out, where the bar break was building. Those waves always gave long, smooth rides and dumped into deeper water, so the landings were soft.

This day, I felt different forces in the water. It seemed darker and bluer, with whiter foam and stronger winds. The breakers curled up quickly, rearing over me. The tide was higher than it had looked. The bigger waves started to break in deeper water. I was neck deep in the troughs and the current sucked me along.

That's when I noticed the tiny, dancing figure of the life guard. I'd never really noticed the lifeguards on this beach before. I didn't bother them. They didn't bother me. But now I heard a thin little whistle fighting through the rumble of waves and the beating of the wind gusts over the breaking crests. The tiny figure on the tall chair waved urgently, imperatively, gathering me shoreward with his arm. Snap! Snap! It looked like the opposite of throwing a ball.

The current had me. I was on my way to Daytona. Worse than that, I was pissing off the lifeguard. Not good.

Not even a strong swimmer fights a current like that. You need endurance and patience, not explosive power. I lay over in a leisurely side-stroke and angled gently toward shore. The current would let me sidle out if I just took my time.

Once out of the main flow I caught a shore-bound breaker and rode in to a belly-landing on the beach. I walked about a quarter-mile back to the car.

It seemed like a good day to stay dry and work on the old tan. But I was glad I'd at least given the waves a try. It was a good little trip.

Tuesday, May 24, 2005

This is more or less actually how it went down that April day in 1988 beside New Hampshire's Swift River.

Posted by Hello

Your brain goes funny when you're cooped up in a gear store all day. This seemed like the next big thing in packs to me.

Posted by Hello

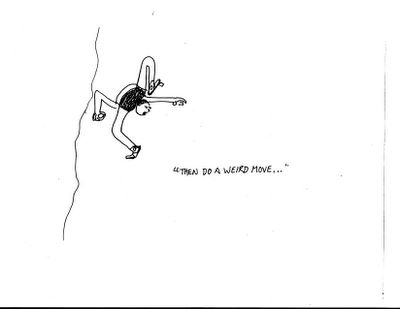

This line appears in some climbing route descriptions. How weird is the move, anyway?

Posted by Hello

Climbers may have a sense of humor, but they don't seem to have MY sense of humor. No one really thought this was funny. I still do.

Posted by Hello

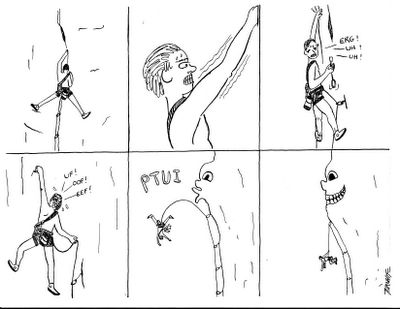

This is for a friend of mine who used to say the route "spit him out" if he failed on it.

Posted by Hello

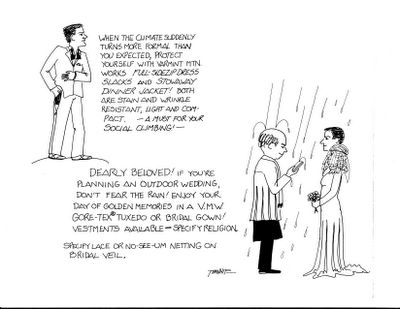

Selections from the Varmint Mountain Works catalog. I think Patagonia actually made this stuff eventually.

Posted by Hello

Tuesday, May 17, 2005

Rotation

Labor Day Weekend in 1987, I was up on Mount Adams, in New Hampshire's Presidential Range, planning to bivouac above treeline, because I'd heard there might be northern lights.

Labor Day Weekend. I wouldn't have had a chance at a spot in one of the huts anyway. But I felt comfortable both in gear and conscience, planning to sleep out up high. I would nestle my sleeping bag in a cleft on the rocks, not on sensitive vegetation. I wouldn't put up a colorful tent and try to make myself at home. I'd brought a small stove, but only to make hot drinks, not an elaborate meal. I was there to get into the place, not reshape it.

My journal for the day notes, "5:30 p.m. -- Awesome! Sundogs! Prismatic flashes at 12, 9 , 3 o'clock around the sun. A ring of light connects them."

The display grew more and more elaborate. My journal entry degrades quickly into awestruck profanity. I will omit that.

"There are now three rings of rainbow in sections with an inverted one above 12 o'clock. This is why I come to places like this! Spotlights of pure white light beam out from 9 and 3.

"The sun's brightness fluctuates as it sinks through cloud layers of different density. It is all cirrus, but some is thicker. The beams aim off like searchlights. The outer rainbow brightens and pales, too.

"Sundogs are an arctic phenomenon. I wonder if this is a good omen for another arctic phenomenon I'd like to see.

"The sun seems to be standing still. There is over an hour of daylight left. People are leaving, although there are quite a few up on Adams. Down here on Sam, I have my own private mountain."

The sundogs sank with the sun. The upper rainbows faded away. Adams looked deserted.

"Soon I'll be left alone with the wild, high night," I wrote.

The right-hand dog sent its beam miles to the west.

"Among all the gray rocks are sudden white ones, white as the bags from a bakery. This simile intensifies, the more hungry the viewer becomes. Below me stands a cairn made entirely of these white stones."

I regretted slightly my choice to forego much in the way of food.

The ridges purpled with the coming darkness. The hazy sky softened all shadows. It was so cool, I felt selfish being alone in it.

"The moon will be up not long after sunset, if it isn't hiding out up there in the cirrostratus already. Sunset is shaping up to be about a 4.5. No more dogs.

"6:55 p.m. --All that remains of the sun is an orange glow between gray and mauve clouds. Not a warming sight, but at least it isn't a stormy yellow.

"I feel like howling a wolf-howl. I may treat the huts within earshot to a banshee wail."

I didn't do that. My natural urge to hide overcame the surge of feral exultation.

Then, when I thought the show was completely over, the sun dropped below the clouds and hung there, an orange disk. I could look almost directly at it as it moved toward the horizon. And I saw the horizon was below me. Even as I absorbed that, I saw, clearly saw, that the disk of the sun was not dropping, it was receding.

We all know the Earth turns and the sun stays in place. But how often do you really get a look at the motion as rotation?

As the cliche goes, I felt the Earth move. I felt it roll away from me, like I was beginning a long, slow back flip. As soon as the sun had set I swiveled around to face east and wait for it to come around again. It was like a huge, cool ride.

Labor Day Weekend. I wouldn't have had a chance at a spot in one of the huts anyway. But I felt comfortable both in gear and conscience, planning to sleep out up high. I would nestle my sleeping bag in a cleft on the rocks, not on sensitive vegetation. I wouldn't put up a colorful tent and try to make myself at home. I'd brought a small stove, but only to make hot drinks, not an elaborate meal. I was there to get into the place, not reshape it.

My journal for the day notes, "5:30 p.m. -- Awesome! Sundogs! Prismatic flashes at 12, 9 , 3 o'clock around the sun. A ring of light connects them."

The display grew more and more elaborate. My journal entry degrades quickly into awestruck profanity. I will omit that.

"There are now three rings of rainbow in sections with an inverted one above 12 o'clock. This is why I come to places like this! Spotlights of pure white light beam out from 9 and 3.

"The sun's brightness fluctuates as it sinks through cloud layers of different density. It is all cirrus, but some is thicker. The beams aim off like searchlights. The outer rainbow brightens and pales, too.

"Sundogs are an arctic phenomenon. I wonder if this is a good omen for another arctic phenomenon I'd like to see.

"The sun seems to be standing still. There is over an hour of daylight left. People are leaving, although there are quite a few up on Adams. Down here on Sam, I have my own private mountain."

The sundogs sank with the sun. The upper rainbows faded away. Adams looked deserted.

"Soon I'll be left alone with the wild, high night," I wrote.

The right-hand dog sent its beam miles to the west.

"Among all the gray rocks are sudden white ones, white as the bags from a bakery. This simile intensifies, the more hungry the viewer becomes. Below me stands a cairn made entirely of these white stones."

I regretted slightly my choice to forego much in the way of food.

The ridges purpled with the coming darkness. The hazy sky softened all shadows. It was so cool, I felt selfish being alone in it.

"The moon will be up not long after sunset, if it isn't hiding out up there in the cirrostratus already. Sunset is shaping up to be about a 4.5. No more dogs.

"6:55 p.m. --All that remains of the sun is an orange glow between gray and mauve clouds. Not a warming sight, but at least it isn't a stormy yellow.

"I feel like howling a wolf-howl. I may treat the huts within earshot to a banshee wail."

I didn't do that. My natural urge to hide overcame the surge of feral exultation.

Then, when I thought the show was completely over, the sun dropped below the clouds and hung there, an orange disk. I could look almost directly at it as it moved toward the horizon. And I saw the horizon was below me. Even as I absorbed that, I saw, clearly saw, that the disk of the sun was not dropping, it was receding.

We all know the Earth turns and the sun stays in place. But how often do you really get a look at the motion as rotation?

As the cliche goes, I felt the Earth move. I felt it roll away from me, like I was beginning a long, slow back flip. As soon as the sun had set I swiveled around to face east and wait for it to come around again. It was like a huge, cool ride.

Paddling Winni

New Hampshire's freshwater paddling season is barely underway, but the time before and after the height of summer is the easiest time to paddle freely on lakes like Winnipesaukee, ringed as they are with private property.

The time before July 4 and after Labor Day is Local Summer, when the locals can enjoy the area with the least conflict with the paying guests whose outdoor habits can be annoying at best, and hazardous at worst.

It's the time for commando expeditions, camping cold and dark on shorefront not technically your own. Shhh. Don't tell anyone. It takes minimum impact methods to new heights.

Particularly in the early season, seemingly unoccupied islands and shorefront may host nesting birds, so the commando paddler must watch carefully.

I don't recommend night paddling during the height of summer. Summer homes are more likely to be occupied. And the drunks in absurd powerboats have enough trouble missing each other, let alone low, dark, silent craft propelled by lunatics and peabrains who actually like to exert themselves to get around.

I've paddled at night in peak season. Stick to the fringes, behind or under stationary objects that will intercept the misguided missile. Just remember that on more than one occasion a hurtling drunk has rammed 20-odd feet of powerboat completely out of the water onto an island he happened to overlook.

In daylight the situation is marginally better. Avoid exposure as much as possible. Get exposed crossings out of the way quickly. If you have a big flotilla, keep it together, but choose an efficient course and encourage people to hold to it, at the best maintainable speed.

It's a little different from wrangling traffic on a bicycle. Vessels can close in on each other from widely varying angles, without the channeling of the street and the familiar guidance of traffic signals and rules. Some idiot with the bow up may not ever see you asserting your rights down there, even in daylight.

I take advantage of the small vessel's ability to exploit small spaces. I play with the conditions, like surf around the end of Tuftonboro Neck on windy days, where I can duck into shelter to escape a passing speedboat or take a breather from the waves. Island hop. Work the shoreline. Save the big crossings for the quieter time of year.

The time before July 4 and after Labor Day is Local Summer, when the locals can enjoy the area with the least conflict with the paying guests whose outdoor habits can be annoying at best, and hazardous at worst.

It's the time for commando expeditions, camping cold and dark on shorefront not technically your own. Shhh. Don't tell anyone. It takes minimum impact methods to new heights.

Particularly in the early season, seemingly unoccupied islands and shorefront may host nesting birds, so the commando paddler must watch carefully.

I don't recommend night paddling during the height of summer. Summer homes are more likely to be occupied. And the drunks in absurd powerboats have enough trouble missing each other, let alone low, dark, silent craft propelled by lunatics and peabrains who actually like to exert themselves to get around.

I've paddled at night in peak season. Stick to the fringes, behind or under stationary objects that will intercept the misguided missile. Just remember that on more than one occasion a hurtling drunk has rammed 20-odd feet of powerboat completely out of the water onto an island he happened to overlook.

In daylight the situation is marginally better. Avoid exposure as much as possible. Get exposed crossings out of the way quickly. If you have a big flotilla, keep it together, but choose an efficient course and encourage people to hold to it, at the best maintainable speed.

It's a little different from wrangling traffic on a bicycle. Vessels can close in on each other from widely varying angles, without the channeling of the street and the familiar guidance of traffic signals and rules. Some idiot with the bow up may not ever see you asserting your rights down there, even in daylight.

I take advantage of the small vessel's ability to exploit small spaces. I play with the conditions, like surf around the end of Tuftonboro Neck on windy days, where I can duck into shelter to escape a passing speedboat or take a breather from the waves. Island hop. Work the shoreline. Save the big crossings for the quieter time of year.

Wind, Waves and Moonlight

The sun had set, but its red fire was still strong as Jim and I paddled out beyond Sewall Point and got a view down the broads of Lake Winnipesaukee on an evening at the end of September 1998. We watched the color spread across the western sky and subside. The waves lost their pink tops and shaded down through slate to darker blues.

Sunset did not bring calm that night. We met increasing winds. The waves subtly mounted. We speared into them and leaped over as we fought the wind. Both wind and wave grew stronger with every headland we passed.

We intended to paddle down to the end of Wolfeboro Neck and back, just a short, leisurely evening jaunt. The water was quite warm, with summer barely over, but we knew the air would cool quickly with darkness. We wore polypro shirts and paddling jackets.

All that bouncing around over warm, rushing water started to get to me, so I indicated a need to step ashore for a moment.

Darkness had solidly fallen, but a half moon was spreading a very usable light. We sought a dark spot on the coast of Wolfeboro Neck, where we could land in stealth. No need to attract attention.

The wind and waves kept us focused on safe piloting, but Jim knew a sheltered beach tucked into a tiny cove. A house high above it showed one small, lighted window, but the landing place was too good to pass up. In commando-like silence we paddled delicately to the beach and disembarked. We pulled our boats above the reach of the waves.

With buoyant spirits and empty ballast tanks, we set off again on the moon-silvered water. We could see the gusts of wind as black patches rushing down at us. The waves mounted swiftly.

Wolfeboro Neck bends gently back, exposing the rocky shoreline gradually more and more to the prevailing winds that sweep most strongly up the Broads. We stopped dead when faced with the unbroken power of the waves marching the length of the lake. The tallest easily blocked our sight. We were able to hold our place, paddling just to hold ourselves head on to the big rollers, feeling the gusts. We could see the big sets teamed up with the strongest winds. It did not look like a place to play in the dark on a chilly night, even with the water warmer than the air.

When we turned, we felt the power of the waves at once. We both took off surfing with no conscious effort to catch a wave. The crests frothed with white.

Even at full speed on a big wave I could feel the power of the wind behind me. It did not disappear the way it does on a sailboat.

I got one glimpse of Jim’s long boat, silhouetted against silver moon sparkles, shooting down the face of a big, curling wave at twice his best paddling speed. The slender hull leaped forward, free of the drag of displacement and immersion, thrown forward like a spear against the shining black and silver background. Then a crest flung me forward and I had to chop and yank with my own paddle to keep my boat from broaching.

This was my first season with the Alto, and I was very pleased with its handling. I wasn’t about to take conditions lightly, since they were quite hazardous in the darkness, but I felt confident the boat could take it, if I piloted her correctly.

Jim seemed content to head back in the general direction of Wolfeboro Bay, catching great wave rides, but I tried to stay a little closer to the shore, to gain the gradually increasing shelter it afforded. That seemed prudent. The final blast of wind, from which we had retreated, had been strong enough to provoke genuine respect.

My plan almost showed a serious flaw when I found myself thrashing in a flurry of foam where the big combers reared up and crashed on some shallowing water at the first little point we approached on our retreat. The waves were big enough to break on what would not seem to be a shoal on a calm summer day.

I could dimly make out a breakwater. I thrashed for sea room, taking a couple of breakers across the waist. The water, fortunately not too chilly, sluiced through my cheesy spray skirt and left me sitting in a puddle. I made a mental note to buy a better skirt the next day.

Meanwhile, I had more serious concerns, as the waves seemed determined to put me on shore. I clawed my way out toward Jim.

We continued along the neck, unable to hear each other. I kept an eye on him. He kept an eye on me. We gave each other room to maneuver. We surfed.

Past Edmund’s Cove and Tip’s Cove, the lake had settled, so we could paddle closer and talk to each other. We saw a big point ahead.

“Is that it?” one of us asked. Together we realized it was not Sewall Point and Wolfeboro Bay, but Jockey Cove, which is large and cuts deeply enough that in the past it was a portage point for canoes to cross to Winter Harbor without facing the tumult we had met on the outside passage. Carry Beach, on Winter Harbor, is named for it.

We had let our guards down a bit when suddenly we found ourselves in a bizarre, confused sea with a shrieking wind funneling out of the cove. Because Wolfeboro Neck is fairly high, and the Carry Beach isthmus is barely above lake level, with more high land inland, it took the wind that lashed the length of Winter Harbor, shoved it through the venturi of Carry Beach and spit it out Jockey Cove with its very own steep, assertive wave pattern meeting the lake-long march of waves on which we rode, at a slightly quartering angle with a fierce wind to match.

It was nothing you could surf. To surf it would mean riding out into the big stuff that still rolled down the lake. Where the wave trains met and crossed, they tossed up crests at random, shredded into spindrift by the crosswind.

I set my boat across this mess and stroked for all I was worth, almost entirely on the windward side. I was ahead of Jim, so I couldn’t see him, but I couldn’t worry about that until I’d gotten out of the trap and could look around carefully.

Spray blew right across my boat. The wind was harder than anything we’d met since we poked our noses out around Umbrella Point and had decided to turn back.

As soon as I got beyond the mouth of Jockey Cove, the relatively gentle remnants of the prevailing wind returned the water to the coherent pattern we’d been riding. I spotted Jim. We worked toward each other.

We surfed around Sewall Point, really just surging on the foot-high chop. We could spare a glance then, at little lighted airplanes off to the east, and one small dot that looked like it was probably in orbit. We also saw one good shooting star.

Even though my seat was squishy and clammy from my adventure in the breakers, I was happy to drift there in the shelter of Sewall Point and look at the sky and the shore, and talk about subjects lofty and low. After a while, the chill got to us both and we headed for home.

For rough weather or night maneuvers, paddlers need to know their abilities are pretty close and that they can handle the worst that might happen on that occasion. Obviously you can’t prepare for something like a heart attack or a seizure, but a party of two had better be confident that under most circumstances one won’t have to rescue the other. That way, if things get a little hairy, like they did at Jockey Cove, each paddler can deal with conditions. If paddlers are roughly equal, both will feel like continuing or backing off at about the same time.

Night paddling is risky. With two it is riskier than with three or four. With one it’s not much riskier than with two, except that your death might not be witnessed. So I can’t suggest anybody go out and do it. But we did see some really cool stuff on this and many other night voyages. Make sure your gear is solid, your skills are up and your will is current. And if you don’t feel like taking a risk, don’t. It doesn’t need to be done.

Sunset did not bring calm that night. We met increasing winds. The waves subtly mounted. We speared into them and leaped over as we fought the wind. Both wind and wave grew stronger with every headland we passed.

We intended to paddle down to the end of Wolfeboro Neck and back, just a short, leisurely evening jaunt. The water was quite warm, with summer barely over, but we knew the air would cool quickly with darkness. We wore polypro shirts and paddling jackets.

All that bouncing around over warm, rushing water started to get to me, so I indicated a need to step ashore for a moment.

Darkness had solidly fallen, but a half moon was spreading a very usable light. We sought a dark spot on the coast of Wolfeboro Neck, where we could land in stealth. No need to attract attention.

The wind and waves kept us focused on safe piloting, but Jim knew a sheltered beach tucked into a tiny cove. A house high above it showed one small, lighted window, but the landing place was too good to pass up. In commando-like silence we paddled delicately to the beach and disembarked. We pulled our boats above the reach of the waves.

With buoyant spirits and empty ballast tanks, we set off again on the moon-silvered water. We could see the gusts of wind as black patches rushing down at us. The waves mounted swiftly.

Wolfeboro Neck bends gently back, exposing the rocky shoreline gradually more and more to the prevailing winds that sweep most strongly up the Broads. We stopped dead when faced with the unbroken power of the waves marching the length of the lake. The tallest easily blocked our sight. We were able to hold our place, paddling just to hold ourselves head on to the big rollers, feeling the gusts. We could see the big sets teamed up with the strongest winds. It did not look like a place to play in the dark on a chilly night, even with the water warmer than the air.

When we turned, we felt the power of the waves at once. We both took off surfing with no conscious effort to catch a wave. The crests frothed with white.

Even at full speed on a big wave I could feel the power of the wind behind me. It did not disappear the way it does on a sailboat.

I got one glimpse of Jim’s long boat, silhouetted against silver moon sparkles, shooting down the face of a big, curling wave at twice his best paddling speed. The slender hull leaped forward, free of the drag of displacement and immersion, thrown forward like a spear against the shining black and silver background. Then a crest flung me forward and I had to chop and yank with my own paddle to keep my boat from broaching.

This was my first season with the Alto, and I was very pleased with its handling. I wasn’t about to take conditions lightly, since they were quite hazardous in the darkness, but I felt confident the boat could take it, if I piloted her correctly.

Jim seemed content to head back in the general direction of Wolfeboro Bay, catching great wave rides, but I tried to stay a little closer to the shore, to gain the gradually increasing shelter it afforded. That seemed prudent. The final blast of wind, from which we had retreated, had been strong enough to provoke genuine respect.

My plan almost showed a serious flaw when I found myself thrashing in a flurry of foam where the big combers reared up and crashed on some shallowing water at the first little point we approached on our retreat. The waves were big enough to break on what would not seem to be a shoal on a calm summer day.

I could dimly make out a breakwater. I thrashed for sea room, taking a couple of breakers across the waist. The water, fortunately not too chilly, sluiced through my cheesy spray skirt and left me sitting in a puddle. I made a mental note to buy a better skirt the next day.

Meanwhile, I had more serious concerns, as the waves seemed determined to put me on shore. I clawed my way out toward Jim.

We continued along the neck, unable to hear each other. I kept an eye on him. He kept an eye on me. We gave each other room to maneuver. We surfed.

Past Edmund’s Cove and Tip’s Cove, the lake had settled, so we could paddle closer and talk to each other. We saw a big point ahead.

“Is that it?” one of us asked. Together we realized it was not Sewall Point and Wolfeboro Bay, but Jockey Cove, which is large and cuts deeply enough that in the past it was a portage point for canoes to cross to Winter Harbor without facing the tumult we had met on the outside passage. Carry Beach, on Winter Harbor, is named for it.

We had let our guards down a bit when suddenly we found ourselves in a bizarre, confused sea with a shrieking wind funneling out of the cove. Because Wolfeboro Neck is fairly high, and the Carry Beach isthmus is barely above lake level, with more high land inland, it took the wind that lashed the length of Winter Harbor, shoved it through the venturi of Carry Beach and spit it out Jockey Cove with its very own steep, assertive wave pattern meeting the lake-long march of waves on which we rode, at a slightly quartering angle with a fierce wind to match.

It was nothing you could surf. To surf it would mean riding out into the big stuff that still rolled down the lake. Where the wave trains met and crossed, they tossed up crests at random, shredded into spindrift by the crosswind.

I set my boat across this mess and stroked for all I was worth, almost entirely on the windward side. I was ahead of Jim, so I couldn’t see him, but I couldn’t worry about that until I’d gotten out of the trap and could look around carefully.

Spray blew right across my boat. The wind was harder than anything we’d met since we poked our noses out around Umbrella Point and had decided to turn back.

As soon as I got beyond the mouth of Jockey Cove, the relatively gentle remnants of the prevailing wind returned the water to the coherent pattern we’d been riding. I spotted Jim. We worked toward each other.

We surfed around Sewall Point, really just surging on the foot-high chop. We could spare a glance then, at little lighted airplanes off to the east, and one small dot that looked like it was probably in orbit. We also saw one good shooting star.

Even though my seat was squishy and clammy from my adventure in the breakers, I was happy to drift there in the shelter of Sewall Point and look at the sky and the shore, and talk about subjects lofty and low. After a while, the chill got to us both and we headed for home.

For rough weather or night maneuvers, paddlers need to know their abilities are pretty close and that they can handle the worst that might happen on that occasion. Obviously you can’t prepare for something like a heart attack or a seizure, but a party of two had better be confident that under most circumstances one won’t have to rescue the other. That way, if things get a little hairy, like they did at Jockey Cove, each paddler can deal with conditions. If paddlers are roughly equal, both will feel like continuing or backing off at about the same time.