During my college years in Florida I was an addicted body surfer.

One summer day at New Smyrna Beach, we arrived from Orlando to find the biggest conditons I'd seen yet. The tide was fairly high and the white-crested surf piled up on itself as the waves rumbled ashore. It wasn't storm surf by any means, but it looked more powerful than the usual sea-breeze break of two- or three-footers we usually played out there on the bar.

Once we parked I hopped out, tossed down my towel, stripped to my shorts and sprinted down the sand.

Even the shore break felt powerful, but the good stuff was further out, where the bar break was building. Those waves always gave long, smooth rides and dumped into deeper water, so the landings were soft.

This day, I felt different forces in the water. It seemed darker and bluer, with whiter foam and stronger winds. The breakers curled up quickly, rearing over me. The tide was higher than it had looked. The bigger waves started to break in deeper water. I was neck deep in the troughs and the current sucked me along.

That's when I noticed the tiny, dancing figure of the life guard. I'd never really noticed the lifeguards on this beach before. I didn't bother them. They didn't bother me. But now I heard a thin little whistle fighting through the rumble of waves and the beating of the wind gusts over the breaking crests. The tiny figure on the tall chair waved urgently, imperatively, gathering me shoreward with his arm. Snap! Snap! It looked like the opposite of throwing a ball.

The current had me. I was on my way to Daytona. Worse than that, I was pissing off the lifeguard. Not good.

Not even a strong swimmer fights a current like that. You need endurance and patience, not explosive power. I lay over in a leisurely side-stroke and angled gently toward shore. The current would let me sidle out if I just took my time.

Once out of the main flow I caught a shore-bound breaker and rode in to a belly-landing on the beach. I walked about a quarter-mile back to the car.

It seemed like a good day to stay dry and work on the old tan. But I was glad I'd at least given the waves a try. It was a good little trip.

These are memorable trips short and long by various modes of transportation, true to the best of my recollection.

Tuesday, May 31, 2005

Tuesday, May 24, 2005

This is more or less actually how it went down that April day in 1988 beside New Hampshire's Swift River.

Posted by Hello

Your brain goes funny when you're cooped up in a gear store all day. This seemed like the next big thing in packs to me.

Posted by Hello

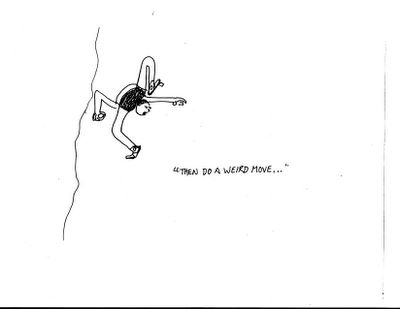

This line appears in some climbing route descriptions. How weird is the move, anyway?

Posted by Hello

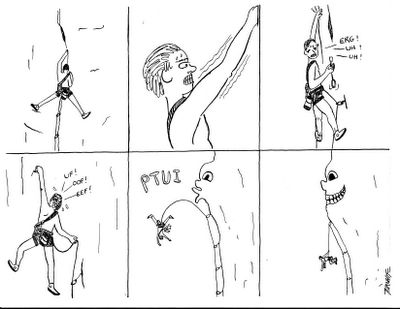

Climbers may have a sense of humor, but they don't seem to have MY sense of humor. No one really thought this was funny. I still do.

Posted by Hello

This is for a friend of mine who used to say the route "spit him out" if he failed on it.

Posted by Hello

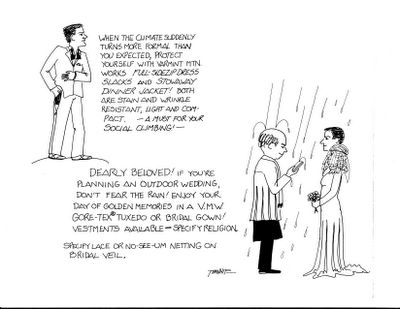

Selections from the Varmint Mountain Works catalog. I think Patagonia actually made this stuff eventually.

Posted by Hello

Tuesday, May 17, 2005

Rotation

Labor Day Weekend in 1987, I was up on Mount Adams, in New Hampshire's Presidential Range, planning to bivouac above treeline, because I'd heard there might be northern lights.

Labor Day Weekend. I wouldn't have had a chance at a spot in one of the huts anyway. But I felt comfortable both in gear and conscience, planning to sleep out up high. I would nestle my sleeping bag in a cleft on the rocks, not on sensitive vegetation. I wouldn't put up a colorful tent and try to make myself at home. I'd brought a small stove, but only to make hot drinks, not an elaborate meal. I was there to get into the place, not reshape it.

My journal for the day notes, "5:30 p.m. -- Awesome! Sundogs! Prismatic flashes at 12, 9 , 3 o'clock around the sun. A ring of light connects them."

The display grew more and more elaborate. My journal entry degrades quickly into awestruck profanity. I will omit that.

"There are now three rings of rainbow in sections with an inverted one above 12 o'clock. This is why I come to places like this! Spotlights of pure white light beam out from 9 and 3.

"The sun's brightness fluctuates as it sinks through cloud layers of different density. It is all cirrus, but some is thicker. The beams aim off like searchlights. The outer rainbow brightens and pales, too.

"Sundogs are an arctic phenomenon. I wonder if this is a good omen for another arctic phenomenon I'd like to see.

"The sun seems to be standing still. There is over an hour of daylight left. People are leaving, although there are quite a few up on Adams. Down here on Sam, I have my own private mountain."

The sundogs sank with the sun. The upper rainbows faded away. Adams looked deserted.

"Soon I'll be left alone with the wild, high night," I wrote.

The right-hand dog sent its beam miles to the west.

"Among all the gray rocks are sudden white ones, white as the bags from a bakery. This simile intensifies, the more hungry the viewer becomes. Below me stands a cairn made entirely of these white stones."

I regretted slightly my choice to forego much in the way of food.

The ridges purpled with the coming darkness. The hazy sky softened all shadows. It was so cool, I felt selfish being alone in it.

"The moon will be up not long after sunset, if it isn't hiding out up there in the cirrostratus already. Sunset is shaping up to be about a 4.5. No more dogs.

"6:55 p.m. --All that remains of the sun is an orange glow between gray and mauve clouds. Not a warming sight, but at least it isn't a stormy yellow.

"I feel like howling a wolf-howl. I may treat the huts within earshot to a banshee wail."

I didn't do that. My natural urge to hide overcame the surge of feral exultation.

Then, when I thought the show was completely over, the sun dropped below the clouds and hung there, an orange disk. I could look almost directly at it as it moved toward the horizon. And I saw the horizon was below me. Even as I absorbed that, I saw, clearly saw, that the disk of the sun was not dropping, it was receding.

We all know the Earth turns and the sun stays in place. But how often do you really get a look at the motion as rotation?

As the cliche goes, I felt the Earth move. I felt it roll away from me, like I was beginning a long, slow back flip. As soon as the sun had set I swiveled around to face east and wait for it to come around again. It was like a huge, cool ride.

Labor Day Weekend. I wouldn't have had a chance at a spot in one of the huts anyway. But I felt comfortable both in gear and conscience, planning to sleep out up high. I would nestle my sleeping bag in a cleft on the rocks, not on sensitive vegetation. I wouldn't put up a colorful tent and try to make myself at home. I'd brought a small stove, but only to make hot drinks, not an elaborate meal. I was there to get into the place, not reshape it.

My journal for the day notes, "5:30 p.m. -- Awesome! Sundogs! Prismatic flashes at 12, 9 , 3 o'clock around the sun. A ring of light connects them."

The display grew more and more elaborate. My journal entry degrades quickly into awestruck profanity. I will omit that.

"There are now three rings of rainbow in sections with an inverted one above 12 o'clock. This is why I come to places like this! Spotlights of pure white light beam out from 9 and 3.

"The sun's brightness fluctuates as it sinks through cloud layers of different density. It is all cirrus, but some is thicker. The beams aim off like searchlights. The outer rainbow brightens and pales, too.

"Sundogs are an arctic phenomenon. I wonder if this is a good omen for another arctic phenomenon I'd like to see.

"The sun seems to be standing still. There is over an hour of daylight left. People are leaving, although there are quite a few up on Adams. Down here on Sam, I have my own private mountain."

The sundogs sank with the sun. The upper rainbows faded away. Adams looked deserted.

"Soon I'll be left alone with the wild, high night," I wrote.

The right-hand dog sent its beam miles to the west.

"Among all the gray rocks are sudden white ones, white as the bags from a bakery. This simile intensifies, the more hungry the viewer becomes. Below me stands a cairn made entirely of these white stones."

I regretted slightly my choice to forego much in the way of food.

The ridges purpled with the coming darkness. The hazy sky softened all shadows. It was so cool, I felt selfish being alone in it.

"The moon will be up not long after sunset, if it isn't hiding out up there in the cirrostratus already. Sunset is shaping up to be about a 4.5. No more dogs.

"6:55 p.m. --All that remains of the sun is an orange glow between gray and mauve clouds. Not a warming sight, but at least it isn't a stormy yellow.

"I feel like howling a wolf-howl. I may treat the huts within earshot to a banshee wail."

I didn't do that. My natural urge to hide overcame the surge of feral exultation.

Then, when I thought the show was completely over, the sun dropped below the clouds and hung there, an orange disk. I could look almost directly at it as it moved toward the horizon. And I saw the horizon was below me. Even as I absorbed that, I saw, clearly saw, that the disk of the sun was not dropping, it was receding.

We all know the Earth turns and the sun stays in place. But how often do you really get a look at the motion as rotation?

As the cliche goes, I felt the Earth move. I felt it roll away from me, like I was beginning a long, slow back flip. As soon as the sun had set I swiveled around to face east and wait for it to come around again. It was like a huge, cool ride.

Paddling Winni

New Hampshire's freshwater paddling season is barely underway, but the time before and after the height of summer is the easiest time to paddle freely on lakes like Winnipesaukee, ringed as they are with private property.

The time before July 4 and after Labor Day is Local Summer, when the locals can enjoy the area with the least conflict with the paying guests whose outdoor habits can be annoying at best, and hazardous at worst.

It's the time for commando expeditions, camping cold and dark on shorefront not technically your own. Shhh. Don't tell anyone. It takes minimum impact methods to new heights.

Particularly in the early season, seemingly unoccupied islands and shorefront may host nesting birds, so the commando paddler must watch carefully.

I don't recommend night paddling during the height of summer. Summer homes are more likely to be occupied. And the drunks in absurd powerboats have enough trouble missing each other, let alone low, dark, silent craft propelled by lunatics and peabrains who actually like to exert themselves to get around.

I've paddled at night in peak season. Stick to the fringes, behind or under stationary objects that will intercept the misguided missile. Just remember that on more than one occasion a hurtling drunk has rammed 20-odd feet of powerboat completely out of the water onto an island he happened to overlook.

In daylight the situation is marginally better. Avoid exposure as much as possible. Get exposed crossings out of the way quickly. If you have a big flotilla, keep it together, but choose an efficient course and encourage people to hold to it, at the best maintainable speed.

It's a little different from wrangling traffic on a bicycle. Vessels can close in on each other from widely varying angles, without the channeling of the street and the familiar guidance of traffic signals and rules. Some idiot with the bow up may not ever see you asserting your rights down there, even in daylight.

I take advantage of the small vessel's ability to exploit small spaces. I play with the conditions, like surf around the end of Tuftonboro Neck on windy days, where I can duck into shelter to escape a passing speedboat or take a breather from the waves. Island hop. Work the shoreline. Save the big crossings for the quieter time of year.

The time before July 4 and after Labor Day is Local Summer, when the locals can enjoy the area with the least conflict with the paying guests whose outdoor habits can be annoying at best, and hazardous at worst.

It's the time for commando expeditions, camping cold and dark on shorefront not technically your own. Shhh. Don't tell anyone. It takes minimum impact methods to new heights.

Particularly in the early season, seemingly unoccupied islands and shorefront may host nesting birds, so the commando paddler must watch carefully.

I don't recommend night paddling during the height of summer. Summer homes are more likely to be occupied. And the drunks in absurd powerboats have enough trouble missing each other, let alone low, dark, silent craft propelled by lunatics and peabrains who actually like to exert themselves to get around.

I've paddled at night in peak season. Stick to the fringes, behind or under stationary objects that will intercept the misguided missile. Just remember that on more than one occasion a hurtling drunk has rammed 20-odd feet of powerboat completely out of the water onto an island he happened to overlook.

In daylight the situation is marginally better. Avoid exposure as much as possible. Get exposed crossings out of the way quickly. If you have a big flotilla, keep it together, but choose an efficient course and encourage people to hold to it, at the best maintainable speed.

It's a little different from wrangling traffic on a bicycle. Vessels can close in on each other from widely varying angles, without the channeling of the street and the familiar guidance of traffic signals and rules. Some idiot with the bow up may not ever see you asserting your rights down there, even in daylight.

I take advantage of the small vessel's ability to exploit small spaces. I play with the conditions, like surf around the end of Tuftonboro Neck on windy days, where I can duck into shelter to escape a passing speedboat or take a breather from the waves. Island hop. Work the shoreline. Save the big crossings for the quieter time of year.

Wind, Waves and Moonlight

The sun had set, but its red fire was still strong as Jim and I paddled out beyond Sewall Point and got a view down the broads of Lake Winnipesaukee on an evening at the end of September 1998. We watched the color spread across the western sky and subside. The waves lost their pink tops and shaded down through slate to darker blues.

Sunset did not bring calm that night. We met increasing winds. The waves subtly mounted. We speared into them and leaped over as we fought the wind. Both wind and wave grew stronger with every headland we passed.

We intended to paddle down to the end of Wolfeboro Neck and back, just a short, leisurely evening jaunt. The water was quite warm, with summer barely over, but we knew the air would cool quickly with darkness. We wore polypro shirts and paddling jackets.

All that bouncing around over warm, rushing water started to get to me, so I indicated a need to step ashore for a moment.

Darkness had solidly fallen, but a half moon was spreading a very usable light. We sought a dark spot on the coast of Wolfeboro Neck, where we could land in stealth. No need to attract attention.

The wind and waves kept us focused on safe piloting, but Jim knew a sheltered beach tucked into a tiny cove. A house high above it showed one small, lighted window, but the landing place was too good to pass up. In commando-like silence we paddled delicately to the beach and disembarked. We pulled our boats above the reach of the waves.

With buoyant spirits and empty ballast tanks, we set off again on the moon-silvered water. We could see the gusts of wind as black patches rushing down at us. The waves mounted swiftly.

Wolfeboro Neck bends gently back, exposing the rocky shoreline gradually more and more to the prevailing winds that sweep most strongly up the Broads. We stopped dead when faced with the unbroken power of the waves marching the length of the lake. The tallest easily blocked our sight. We were able to hold our place, paddling just to hold ourselves head on to the big rollers, feeling the gusts. We could see the big sets teamed up with the strongest winds. It did not look like a place to play in the dark on a chilly night, even with the water warmer than the air.

When we turned, we felt the power of the waves at once. We both took off surfing with no conscious effort to catch a wave. The crests frothed with white.

Even at full speed on a big wave I could feel the power of the wind behind me. It did not disappear the way it does on a sailboat.

I got one glimpse of Jim’s long boat, silhouetted against silver moon sparkles, shooting down the face of a big, curling wave at twice his best paddling speed. The slender hull leaped forward, free of the drag of displacement and immersion, thrown forward like a spear against the shining black and silver background. Then a crest flung me forward and I had to chop and yank with my own paddle to keep my boat from broaching.

This was my first season with the Alto, and I was very pleased with its handling. I wasn’t about to take conditions lightly, since they were quite hazardous in the darkness, but I felt confident the boat could take it, if I piloted her correctly.

Jim seemed content to head back in the general direction of Wolfeboro Bay, catching great wave rides, but I tried to stay a little closer to the shore, to gain the gradually increasing shelter it afforded. That seemed prudent. The final blast of wind, from which we had retreated, had been strong enough to provoke genuine respect.

My plan almost showed a serious flaw when I found myself thrashing in a flurry of foam where the big combers reared up and crashed on some shallowing water at the first little point we approached on our retreat. The waves were big enough to break on what would not seem to be a shoal on a calm summer day.

I could dimly make out a breakwater. I thrashed for sea room, taking a couple of breakers across the waist. The water, fortunately not too chilly, sluiced through my cheesy spray skirt and left me sitting in a puddle. I made a mental note to buy a better skirt the next day.

Meanwhile, I had more serious concerns, as the waves seemed determined to put me on shore. I clawed my way out toward Jim.

We continued along the neck, unable to hear each other. I kept an eye on him. He kept an eye on me. We gave each other room to maneuver. We surfed.

Past Edmund’s Cove and Tip’s Cove, the lake had settled, so we could paddle closer and talk to each other. We saw a big point ahead.

“Is that it?” one of us asked. Together we realized it was not Sewall Point and Wolfeboro Bay, but Jockey Cove, which is large and cuts deeply enough that in the past it was a portage point for canoes to cross to Winter Harbor without facing the tumult we had met on the outside passage. Carry Beach, on Winter Harbor, is named for it.

We had let our guards down a bit when suddenly we found ourselves in a bizarre, confused sea with a shrieking wind funneling out of the cove. Because Wolfeboro Neck is fairly high, and the Carry Beach isthmus is barely above lake level, with more high land inland, it took the wind that lashed the length of Winter Harbor, shoved it through the venturi of Carry Beach and spit it out Jockey Cove with its very own steep, assertive wave pattern meeting the lake-long march of waves on which we rode, at a slightly quartering angle with a fierce wind to match.

It was nothing you could surf. To surf it would mean riding out into the big stuff that still rolled down the lake. Where the wave trains met and crossed, they tossed up crests at random, shredded into spindrift by the crosswind.

I set my boat across this mess and stroked for all I was worth, almost entirely on the windward side. I was ahead of Jim, so I couldn’t see him, but I couldn’t worry about that until I’d gotten out of the trap and could look around carefully.

Spray blew right across my boat. The wind was harder than anything we’d met since we poked our noses out around Umbrella Point and had decided to turn back.

As soon as I got beyond the mouth of Jockey Cove, the relatively gentle remnants of the prevailing wind returned the water to the coherent pattern we’d been riding. I spotted Jim. We worked toward each other.

We surfed around Sewall Point, really just surging on the foot-high chop. We could spare a glance then, at little lighted airplanes off to the east, and one small dot that looked like it was probably in orbit. We also saw one good shooting star.

Even though my seat was squishy and clammy from my adventure in the breakers, I was happy to drift there in the shelter of Sewall Point and look at the sky and the shore, and talk about subjects lofty and low. After a while, the chill got to us both and we headed for home.

For rough weather or night maneuvers, paddlers need to know their abilities are pretty close and that they can handle the worst that might happen on that occasion. Obviously you can’t prepare for something like a heart attack or a seizure, but a party of two had better be confident that under most circumstances one won’t have to rescue the other. That way, if things get a little hairy, like they did at Jockey Cove, each paddler can deal with conditions. If paddlers are roughly equal, both will feel like continuing or backing off at about the same time.

Night paddling is risky. With two it is riskier than with three or four. With one it’s not much riskier than with two, except that your death might not be witnessed. So I can’t suggest anybody go out and do it. But we did see some really cool stuff on this and many other night voyages. Make sure your gear is solid, your skills are up and your will is current. And if you don’t feel like taking a risk, don’t. It doesn’t need to be done.

Sunset did not bring calm that night. We met increasing winds. The waves subtly mounted. We speared into them and leaped over as we fought the wind. Both wind and wave grew stronger with every headland we passed.

We intended to paddle down to the end of Wolfeboro Neck and back, just a short, leisurely evening jaunt. The water was quite warm, with summer barely over, but we knew the air would cool quickly with darkness. We wore polypro shirts and paddling jackets.

All that bouncing around over warm, rushing water started to get to me, so I indicated a need to step ashore for a moment.

Darkness had solidly fallen, but a half moon was spreading a very usable light. We sought a dark spot on the coast of Wolfeboro Neck, where we could land in stealth. No need to attract attention.

The wind and waves kept us focused on safe piloting, but Jim knew a sheltered beach tucked into a tiny cove. A house high above it showed one small, lighted window, but the landing place was too good to pass up. In commando-like silence we paddled delicately to the beach and disembarked. We pulled our boats above the reach of the waves.

With buoyant spirits and empty ballast tanks, we set off again on the moon-silvered water. We could see the gusts of wind as black patches rushing down at us. The waves mounted swiftly.

Wolfeboro Neck bends gently back, exposing the rocky shoreline gradually more and more to the prevailing winds that sweep most strongly up the Broads. We stopped dead when faced with the unbroken power of the waves marching the length of the lake. The tallest easily blocked our sight. We were able to hold our place, paddling just to hold ourselves head on to the big rollers, feeling the gusts. We could see the big sets teamed up with the strongest winds. It did not look like a place to play in the dark on a chilly night, even with the water warmer than the air.

When we turned, we felt the power of the waves at once. We both took off surfing with no conscious effort to catch a wave. The crests frothed with white.

Even at full speed on a big wave I could feel the power of the wind behind me. It did not disappear the way it does on a sailboat.

I got one glimpse of Jim’s long boat, silhouetted against silver moon sparkles, shooting down the face of a big, curling wave at twice his best paddling speed. The slender hull leaped forward, free of the drag of displacement and immersion, thrown forward like a spear against the shining black and silver background. Then a crest flung me forward and I had to chop and yank with my own paddle to keep my boat from broaching.

This was my first season with the Alto, and I was very pleased with its handling. I wasn’t about to take conditions lightly, since they were quite hazardous in the darkness, but I felt confident the boat could take it, if I piloted her correctly.

Jim seemed content to head back in the general direction of Wolfeboro Bay, catching great wave rides, but I tried to stay a little closer to the shore, to gain the gradually increasing shelter it afforded. That seemed prudent. The final blast of wind, from which we had retreated, had been strong enough to provoke genuine respect.

My plan almost showed a serious flaw when I found myself thrashing in a flurry of foam where the big combers reared up and crashed on some shallowing water at the first little point we approached on our retreat. The waves were big enough to break on what would not seem to be a shoal on a calm summer day.

I could dimly make out a breakwater. I thrashed for sea room, taking a couple of breakers across the waist. The water, fortunately not too chilly, sluiced through my cheesy spray skirt and left me sitting in a puddle. I made a mental note to buy a better skirt the next day.

Meanwhile, I had more serious concerns, as the waves seemed determined to put me on shore. I clawed my way out toward Jim.

We continued along the neck, unable to hear each other. I kept an eye on him. He kept an eye on me. We gave each other room to maneuver. We surfed.

Past Edmund’s Cove and Tip’s Cove, the lake had settled, so we could paddle closer and talk to each other. We saw a big point ahead.

“Is that it?” one of us asked. Together we realized it was not Sewall Point and Wolfeboro Bay, but Jockey Cove, which is large and cuts deeply enough that in the past it was a portage point for canoes to cross to Winter Harbor without facing the tumult we had met on the outside passage. Carry Beach, on Winter Harbor, is named for it.

We had let our guards down a bit when suddenly we found ourselves in a bizarre, confused sea with a shrieking wind funneling out of the cove. Because Wolfeboro Neck is fairly high, and the Carry Beach isthmus is barely above lake level, with more high land inland, it took the wind that lashed the length of Winter Harbor, shoved it through the venturi of Carry Beach and spit it out Jockey Cove with its very own steep, assertive wave pattern meeting the lake-long march of waves on which we rode, at a slightly quartering angle with a fierce wind to match.

It was nothing you could surf. To surf it would mean riding out into the big stuff that still rolled down the lake. Where the wave trains met and crossed, they tossed up crests at random, shredded into spindrift by the crosswind.

I set my boat across this mess and stroked for all I was worth, almost entirely on the windward side. I was ahead of Jim, so I couldn’t see him, but I couldn’t worry about that until I’d gotten out of the trap and could look around carefully.

Spray blew right across my boat. The wind was harder than anything we’d met since we poked our noses out around Umbrella Point and had decided to turn back.

As soon as I got beyond the mouth of Jockey Cove, the relatively gentle remnants of the prevailing wind returned the water to the coherent pattern we’d been riding. I spotted Jim. We worked toward each other.

We surfed around Sewall Point, really just surging on the foot-high chop. We could spare a glance then, at little lighted airplanes off to the east, and one small dot that looked like it was probably in orbit. We also saw one good shooting star.

Even though my seat was squishy and clammy from my adventure in the breakers, I was happy to drift there in the shelter of Sewall Point and look at the sky and the shore, and talk about subjects lofty and low. After a while, the chill got to us both and we headed for home.

For rough weather or night maneuvers, paddlers need to know their abilities are pretty close and that they can handle the worst that might happen on that occasion. Obviously you can’t prepare for something like a heart attack or a seizure, but a party of two had better be confident that under most circumstances one won’t have to rescue the other. That way, if things get a little hairy, like they did at Jockey Cove, each paddler can deal with conditions. If paddlers are roughly equal, both will feel like continuing or backing off at about the same time.

Night paddling is risky. With two it is riskier than with three or four. With one it’s not much riskier than with two, except that your death might not be witnessed. So I can’t suggest anybody go out and do it. But we did see some really cool stuff on this and many other night voyages. Make sure your gear is solid, your skills are up and your will is current. And if you don’t feel like taking a risk, don’t. It doesn’t need to be done.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)